An Illustrated Lexicon for Democracy Defense

Part I: Anarchy, Autogolpe, Coup, Domestic Terrorism, High Crimes & Misdemeanors, Insurrection, Putsch, Sedition & Seditious Conspiracy, Treason

Today’s newsletter is the first in a series about words being used to describe the events that unfolded at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Sources include: Merriam Webster Collegiate Edition Dictionary, Oxford Languages; and Origins: An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, by Eric Partridge.

Anarchy

“A state of disorder due to absence or nonrecognition of authority.” From Greek, “without a ruler.”

Anarchy ensued on January 6, after Trump supporters, urged by the president to march from a rally on the National Mall to the Capitol, became a lawless mob that illegally trespassed; disrupted a constitutionally mandated procedure in the certification of a presidential election; damaged, destroyed, and stole federal property; assaulted law-enforcement officers (killing one and injuring over fifty); threatened the safety and lives of elected officials and journalists; and called for the execution of the vice-president and the speaker of the house.

Authorities who might have dispatched reinforcements for the overwhelmed Capitol and Metro police might have also urged the rioters to cease and desist. This failure to act contributed to the development of a state of anarchy to develop, which in turn fueled an insurrection (see below), which, we learned later, was part of a planned coup (see below).

Note: Anarchy as a political ideology will be defined in a forthcoming section of the lexicon.

AUTOGOLPE — COUP D’ETAT — PUTSCH

Three words have been used to describe the events of January 6, 2021—autogolpe, coup (d’état), and putsch—all of which echo historical events worth our attention.

Autogolpe

According to Christopher Ingraham, writing in the Washington Post, an autogolpe, or self-coup or auto-coup:

“[…] happens when a head of government, like a president or prime minister, attempts to seize extraordinary control over that government from within. That could mean suspending the Constitution, for instance, dissolving a legislative body or overturning the results of an otherwise free and fair election.

“The term autogolpe originates in Latin America, where a number of infamous self-coups took place in the 20th century.”

Technically, on January 6, we witnessed a failed autogolpe, prepared years before the 2020 election with a disinformation campaign comprising the articulation, propagation, reiteration, amplification, and dissemination of lies about the legitimacy of elections in general and about mail-in voting, ballot theft, and voting fraud during the 2020 presidential election in particular.

Coup (d’état)

The literal translation of this French term is “a strike against the state.” In English we often abbreviate the term to coup, defined as “the violent overthrow or alteration of an existing government by a small group” and “a sudden, violent, and illegal seizure of power from a government.” From Old French, “to hit or strike.”

See also: Is This a Coup’s Coup-o-Meter

Putsch

“A secretly plotted and suddenly executed attempt to overthrow a government” (i.e., a coup d’état). From German, “revolt”; “riot,” derived from Swiss dialect, literally “a sudden blow, push, thrust, shock.”

Putsch debuted in English shortly before Wolfgang Kapp and his right-wing supporters attempted—and failed—to overthrow the German Weimar government in 1920 (this coup failed because labor unions instituted a general strike, and civil servants refused to follow Kapp’s orders). Because putsch attempts were common at the time in Germany, English journalists used it to describe the insurrections.

A notable historical memory: In November 1923, a relatively unknown, thirty-four-year-old Adolf Hitler attempted a putsch, known as the Beer Hall or Munich Putsch, in which approximately two thousand Nazis marched on the Feldhernhalle, a monumental loggia in the city’s center that commemorates the Bavarian Army. Sixteen Nazi Party members and four police officers died. Hitler was wounded and escaped, but then arrested two days later and charged with treason. After a highly publicized twenty-four day trial—at which he expressed his nationalist inclinations and came to world attention—he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to five years in Landsberg Prison. Imprisoned there in relatively comfortable quarters, he dictated Mein Kampf [My Struggle] to two fellow prisoners. Once released, he dedicated himself to becoming the leader of the German government, which he accomplished ten years after the Beer Hall Putsch. Twelve years later, in 1935, he presided over the implementation of the Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews and other minorities of their citizenship and civil rights. The November Pogroms commonly called Kristallnacht took place on 8-9 November 1938, on the fifteenth anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. These pogroms involved the assault and murder of Jewish people and the theft, vandalism, and destruction of their property and houses of worship.

Domestic terrorism

Domestic terrorism is defined as “the committing of terrorist acts in the perpetrator's own country against their fellow citizens.” Terrorism is also defined as “the unlawful use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims.”

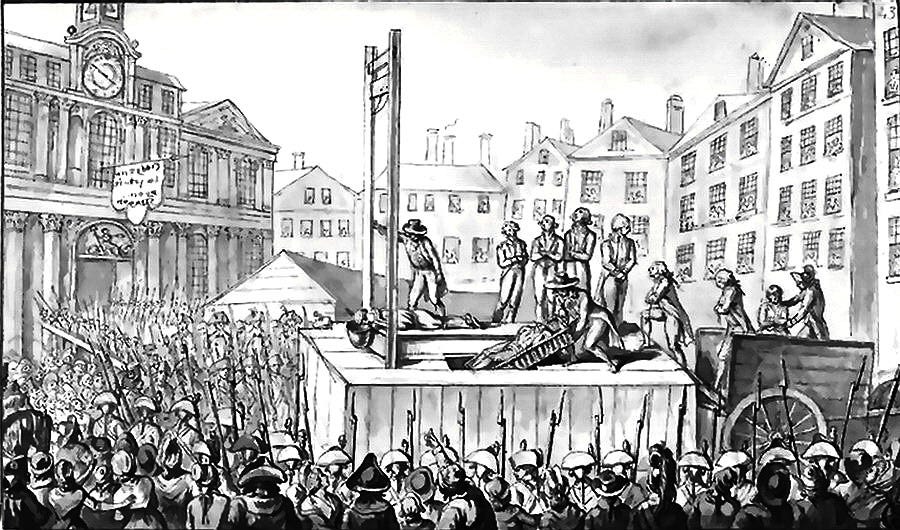

The word terrorism dates back to eighteenth-century France and the post-revolutionary terror meted out by the Jacobins against the monarchist adversaries they had defeated. The word has since evolved to mean “a state of being terrified, or a state impressing terror” (1840). The word terrorist was first defined in American English in Webster’s in 1864 and referred specifically to this episode in French history: “An agent or partisan of the revolutionary tribunal during the reign of terror in France.” In America during the 1920s, the word terrorism was often used stripped of political association and came to be associated with the violence of gangsters. But well into the twentieth century, the word terrorism still signified “violence perpetrated by a government.” For many Americans,Western Europeans, and Israelis, the word terrorist summons Islamic fundamentalists and thus contributes to the internalization of racist stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims.

In the failed coup attempt of January 6, 2021, the violent, far-wright rioters who broke into the Capitol and threatened their fellow citizens inside the building were doing so illegally in their own country; they were in pursuit of a political aim—to overturn, using violence and intimidation, the 2020 presidential election in Trump’s favor—and thus can be categorized as domestic terrorists.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines domestic terrorism as “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals stemming from domestic influences, such as those of a political, religious, social, racial, or environmental nature.” The FBI distinguishes international terrorism as “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups who are inspired by, or associated with, designated foreign terrorist organizations or nations (state-sponsored).”

It is worth noting that the penalties for domestic terrorism, under § 22–3153 of the District of Columbia Criminal Code, include (these are eight of fourteen penalties):

A person who commits murder of a law enforcement officer or public safety employee that constitutes an act of terrorism shall, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for life without the possibility of release.

A person who commits manslaughter that constitutes an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for life.

A person who commits any assault with intent to kill that constitutes an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not more than 30 years.

A person who commits mayhem or maliciously disfiguring another that constitutes an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not more than 20 years.

A person who commits malicious burning, destruction, or injury of another’s property, if such property is valued at $500,000 or more, that constitutes an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not more than 20 years.

A person who attempts or conspires to commit mayhem or maliciously disfiguring another, arson, or malicious burning, destruction, or injury of another’s property, if such property is valued at $500,000 or more, that constitutes an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment of not more than 15 years.

A person who provides material support or resources for an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not more than 20 years.

A person who solicits material support or resources to commit an act of terrorism may, upon conviction, be punished by imprisonment for not more than 20 years.

For more information about how Section 802 of the U.S. Patriot Act redefined terrorism, see this article from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

See also: “Treat the Attack on the Capitol as Terrorism,” by Michael Paradis, in The Atlantic, January 17, 2021.

High Crimes and Misdemeanors

According to Merriam-Webster, a high crime is one “of infamous nature contrary to public morality but not technically constituting a felony. Specifically: an offense that the U.S. Senate deems to constitute an adequate ground for removal of the president, vice president, or any civil officer as a person unfit to hold public office and deserving of impeachment.”

“Misdemeanor literally means ‘bad behavior toward others.’ This led to parallel usage as both general bad behavior and legal bad behavior. In American law, a misdemeanor is ‘a crime less serious than a felony.’ A felony is defined as ‘a federal crime for which the punishment may be death or imprisonment for more than a year.’ As misdemeanor became more specific, crime became the more general term for any legal offense.

“The phrase ‘high crimes and misdemeanors,’ found in Article Two, Section 4 of the Constitution, has been used in English law since the 14th century, as have other fixed phrases using synonymous terms, such as ‘rules and regulations’ and ‘emoluments and salaries.’ It can be very difficult to distinguish between any of these pairs of words, and their frequent use together renders them less technical in today’s highly specific legal vocabulary. ‘High crimes’ are serious crimes committed by those with some office or rank, and was used in the language describing impeachment proceedings of members of the British Parliament in the 18th century.”

See also; “The Common Misperception about ‘High Crimes and Misdemeanors’,” by Frank L. Bowman III, in The Atlantic, October 22, 2019.

Insurrection

An insurrection is “a violent uprising against an authority or government.” From Latin, “to rise up.”

The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol was an insurrection carried out as part of an attempted (and failed) autogolpe-style coup. Another way of saying this: Insurrectionists attempted a coup—which failed—against the U.S. Government.

Seditious Conspiracy

The word sedition derives from the Latin sēdīre, “to go aside, hence to rebel.”

Seditious conspiracy is defined in U.S. Case Law as follows: “If two or more persons in any State or Territory, or in any place subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, conspire to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States, or to levy war against them, or to oppose by force the authority thereof, or by force to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States, or by force to seize, take, or possess any property of the United States contrary to the authority thereof, they shall each be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both” (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute).

See also: “‘Sedition’: A Complicated History,”Jennifer Schuessler, New York Times, January 7, 2021.

Treason

Treason is defined as “the crime of betraying one's country, especially by attempting to kill the sovereign or overthrow the government.” From Latin, trāditiō, “a handing over.”

While the events of January 6, 2021, meet this definition, they do not meet the legal standard defined in the Treason Clause of the Constitution (Article III, Section 3), whose first paragraph sates:

“Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

According to Paul T. Crane and Deborah Pearlstein, “Treason is a unique offense in our constitutional order—the only crime expressly defined by the Constitution, and applying only to Americans who have betrayed the allegiance they are presumed to owe the United States. While the Constitution’s Framers shared the centuries-old view that all citizens owed a duty of loyalty to their home nation, they included the Treason Clause not so much to underscore the seriousness of such a betrayal, but to guard against the historic use of treason prosecutions by repressive governments to silence otherwise legitimate political opposition. Debate surrounding the Clause at the Constitutional Convention thus focused on ways to narrowly define the offense, and to protect against false or flimsy prosecutions” (“Treason Clause,” Interactive Constitution, Constitution Center).

—Kim Dana Kupperman, Clarksville, MD